The presidential election scheduled for June 18 is not the most absurd election in the history of the Islamic Republic, but it is undoubtedly the least important one since the Islamic Republic came to power. The message of the slogan chanted during December 2017’s uprising, that the era of the fundamentalist and reformist factions is over, is now manifest in the electoral situation faced by the Islamic Republic.

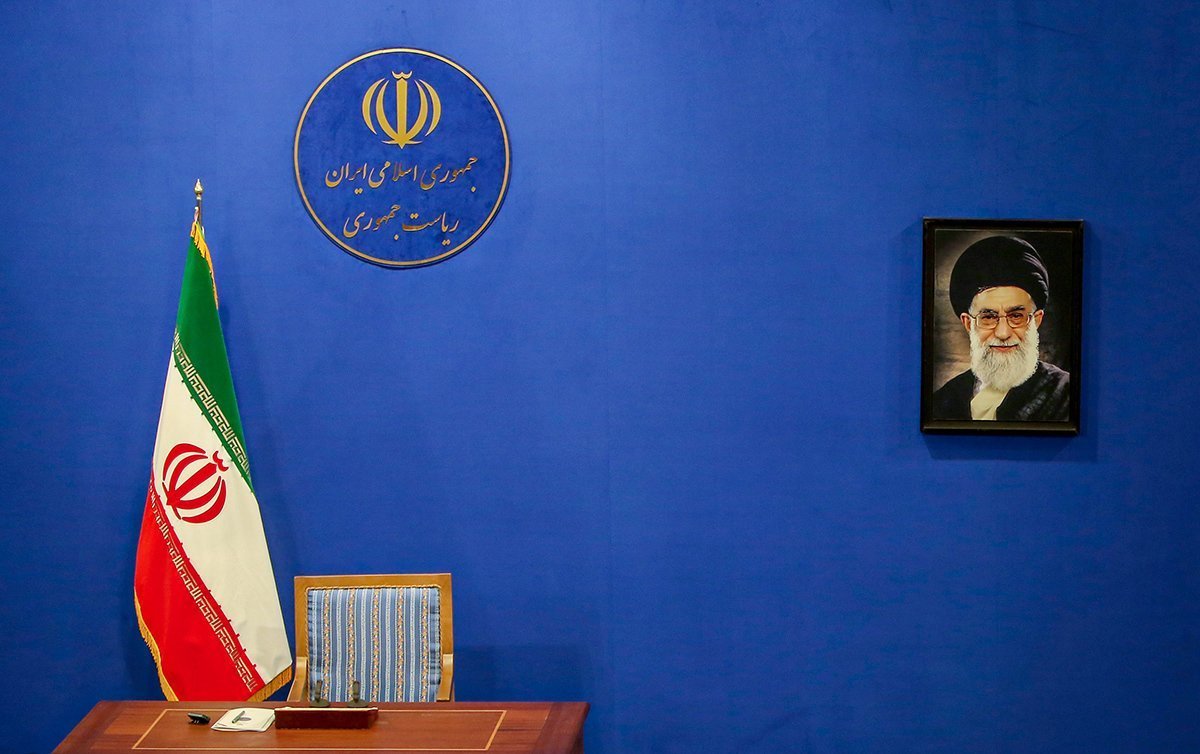

Elections in Iran have always had a rather strange nature. On the one hand, they are an arena of tense competition between the various political factions within the government; and increasingly tense over the life of the Islamic Republic. Yet, the competition is for positions in the government of the Islamic Republic that have virtually no authority, and any violations of the major or minor decisions of the authorities in the Islamic Republic are revoked or amended by non-elected oversight bodies, whose members are often chosen by the Supreme Leader. Although this image is simplistic and does not fully reflect the complexities of the division of power and its internal rivalries and conflicts, it is at least a more accurate picture than that given by Western governments and politicians, in which the “government” of the Islamic Republic has independent decision-making power. This is merely assumed without acknowledging, or maybe even understanding, that there is a state above this government, and the latter can only implement its decisions.

The issue of the government being powerless is not the main problem of the forthcoming election. During the rule of the Islamic Republic, more ridiculous elections than this one were held. For instance, in October 1981, when Iranian opposition groups were brutally suppressed and their members murdered, four presidential candidates from a single party were vying with each other. Just a few days before the election, three of the candidates voluntarily appeared on national TV to announce their support for the fourth presidential candidate, Ali Khamenei. He was close to Ruhollah Khomeini, at that time the supreme leader of the Islamic Republic (the position now held by Khamenei). None of the three candidates withdrew from the election- but all voted for their rival!

The forthcoming election is slightly more competitive than the October 1981 election, as the current candidates do not chant for the others. However, any potentially confrontational figures and former officials of the Islamic Republic, including the former president, vice president, and the former speaker of parliament have been disqualified from running for the presidency. This indicates the Islamic republic has lost the ability to withstand the slightest tension within itself, and prefers to reduce the internal tensions between its own factions at a time when the international situation is turbulent for Iran and public discontent is increasing at every moment.

What is important to focus on in this election is not only the widespread disqualification of candidates, but also the extensive “boycott” propaganda by many opposition forces. A wide range of right- and left-wing opposition forces advocating for the overthrow of the Islamic Republic are strongly campaigning for a boycott of the election. Also, even a range of moderate and reformist critics of the Islamic Republic are protesting this election by not participating, without calling for a boycott. The popularity of a boycott position does not indicate a change in the nature of presidential elections, or a sudden realisation by opposition parties that they are undemocratic and frequently shambolic. Rather, it points to the mass of Iranian society having lost all faith in the republic’s elections as a means to achieve radical political change. The remainder of this article will unfold how this disillusionment has occurred through the history of elections in the Islamic Republic.

In June 2005, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, the populist and right-wing mayor of Tehran won the presidential election, ending the 8-year presidency of a reformist, Mohammad Khatami. Due to widespread dissatisfaction of the urban middle class with government and parliamentary reformers, the June 2005 election was widely “boycotted”. This boycott, however, never meant a rupture from electoral policy and thus the formation of alternative forms of political struggle. In 2005, the people who had hoped for opening up the political space based on the reformists’ promises became disappointed, as none of those promises had been fulfilled. Moreover, the reformist government continued to implement austerity policies which put pressure on the reformists’ main voting base, i.e., the lower middle class.

Electoral policy, nonetheless, maintained its credibility as a means to improve the situation. In subsequent elections, reformist campaigners referred to the results of “sulking” with the ballot box that led to the victory of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, and successfully encouraged people to participate in the elections in favour of candidates of the reformist faction. They did not, however, point out to the electorate that Ahmadinejad’s economic policies were nothing more than the continuation of the economic policies of all the post-war Islamic Republic governments, including that of the government of Mohammad Khatami.

The first nail in the coffin of reform and electoral policy was the victory of Hassan Rouhani in the 2013 election. He was a figure close to Hashemi Rafsanjani’s technocratic, neoconservative faction and supported by all reformist forces. With the establishment of the Rouhani government, the people who previously voted for Rafsanjani’s rhetoric about post-war “reconstruction” and economic prosperity, Mohammad Khatami’s promise of political reform and openness, and Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s noises about equality, finally realized that the policies of austerity which led to the spread of poverty, high prices, and public misery, had nothing to do with any of these various factions of the state. They were the regime’s essential policy that each government had the duty to implement.

These austerity policies were partly related to the development of capitalism in Iran and its need to advance and consolidate policies such as privatisation, price liberalisation including currency, fuel, and energy prices, as well as deregulation of the labour market in favour of capitalists. They were also related to the fulfillment of government obligations to global capital institutions such as the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank, and the World Trade Organization. The imposition of inhumane sanctions by western governments, especially the US government, put more pressure on the lower classes, who were already crumbling because of the government’s economic policies.

In some cases, there are somewhat serious disagreements among the seven people who have been allowed to run for president. Although they all believe in compromise with the international community and de-escalation of the Islamic Republic’s relations with the West, they suggest different ways to achieve this goal. Ultimately, however, it is not the head of government and the plan he announces, but the Islamic Republic that manages Iran’s mode of interaction with the West. All candidates talk about taking immediate actions on the economic conditions: creating jobs, fighting inflation and rising prices, and fighting widespread corruption in all parts of the government, but some of their promises are basically not in the hands of the government, and others are in serious conflict with their own economic ideology. They are all more or less in favour of continuing the policies of privatisation, deregulation, price liberalisation, and the elimination of subsidies.

This commonality exists not only among the seven approved candidates, but even among all of those who were not allowed to run in the election. For example, the former president, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, whose main slogan has been equality, said in an interview (just a few days before the announcement of who is not allowed to run) that he is a “liberal democrat” and the economic policies of his government would likewise be liberal, to show his loyalty to the essential economic policy of the Islamic Republic. In the end, the Islamic Republic’s rulers had other reasons for not allowing the former president to run again.

One consequence of the December 2017 nationwide uprising was the decisive break of the urban poor, the working class, the poor peasants, and the lower layers of the middle class from electoral politics. Not participating in the upcoming elections does not only apply to this section of society of course. Wider sections of society are boycotting the presidential election, but for the working class and the lower classes not voting is not just negative politics, but provides a form of positive alternative as well.

In the past few days, a short video of a young man giving a street speech in the small town of Khomeini Shahr has gone viral on social media. He asks people not to vote in the upcoming elections and emphasizes: “We do not need a president. We can manage our own lives.” Khomeini Shahr, a poor city in the Isfahan Province, was one of the rebel cities during the December 2017 nationwide uprising. At least four people, including a 13-year-old boy, were shot dead during the riot in the town, and five residents have been sentenced to death since the riot was put down, although these death sentences have not yet been carried out. This is however not the only image that shows the true face of the liberation struggles in Iran. At demonstrations in the last few months, at the many rallies and strikes of workers in different sectors, and pensioners, a frequent slogan has been that “we will not vote because we have heard too many lies”. It is of course followed by another slogan that emphasizes that we will reach our rights only in the streets. If one wants to see the true face of liberation struggles in Iran these days beyond the fabricated images broadcast by the mainstream media and understand where the real politics is taking place, instead of staring at the lacklustre ballot box of the Islamic Republic, one should look at the streets; at the endless series of strikes and rallies that form every day in different cities and keep marching forward.

Comment here