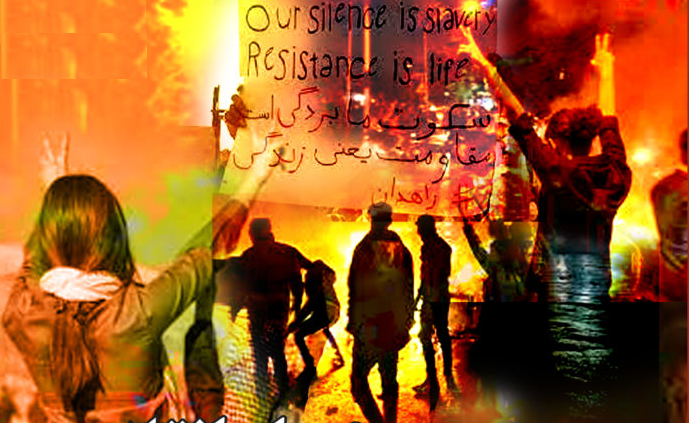

Slingers Collective hosted a series of conversations with active communist committees in Iran discussing the political climate post jina uprising. Part 1 of this conversation already been published here. The committees present at the meeting were as follows: the “Gilan Revolutionary Committee,” which formed during the Jina uprising in several key cities in Gilan province, located in the north of the country and along the Caspian Sea. This committee has been active in organizing demonstrations, distributing leaflets and posters, and establishing communication with the masses and trade unions in the province. The “Javad Nazari Fatahabadi Committee” is a covert committee formed during the November 2019 uprising, and its primary focus has been the establishment of secret cells. The “Red Revolutionary Youth Committee of Mahabad” is a city committee that emerged during the Jina uprising in the city of Mahabad in the Kurdistan region of Iran. It played a pivotal role in the uprising in this city, representing a communist faction in an area historically associated with the largest Kurdish nationalist party. The “Jian Group” is a core group of female fighters that formed in the early days of the Jina uprising and played a crucial role in organizing some of the most significant demonstrations in Tehran. “Street Militants Group” is another committee, predominantly composed of women, with connections to small towns where oppressed ethnic groups from Lor reside. Lastly, the “Zahedan Revolutionary Youth Core” is a committee based in Zahedan, the largest city in the southeastern region of Iran, predominantly inhabited by ethnically oppressed Baloch people. Broadly speaking, all these committees identify as “communist” and seek to establish an alternative around the political notion of council-based governance after the Islamic Republic. However, as the conversation reveals, this political orientation holds different meanings and implications for each of them.

In the following, you can read part 2 of the first meeting.

Street Militants Group (SMG): Regarding our discussion on religion, when our friend said the ideology of the Islamic regime has failed, I wanted to point out another aspect: that Arabophobia has also intensified. Since the Quran is in Arabic, Arabophobia has increased to the extent that, for example, the Mahshahr massacre in November 2019, which has the highest number of fatalities, has been forgotten [Mahshahr is located in Khuzestan Province, where a significant Arab population resides.]. I believe over 400 people were killed. Or the Khuzistan water shortage uprising (The thirsty Uprising), was not supported either. My second point is related to the middle-class poor; some friends mentioned that the middle class didn’t have a significant presence in this movement. I’m not sure what criteria you are using to define the middle class you are referring to but look at the list of casualties. I think those who were killed, like Jina herself, Hadis Najafi, Hamidreza Rouhi and many others, were from the middle class. If we don’t acknowledge this fact, we end up having a negative view of them (their contribution). Of course, I agree that a large portion of revolutionary violence during uprisings like November 2019 came from the lower class and the poor. Ultimately, the working class, the lower class, and the precariat will be the decisive factor. However, we shouldn’t disregard the potential revived in the middle class, especially considering that, as you also mentioned, the middle class is shrinking and getting poorer. Or, as our friend said, we have to advance the struggle on moral grounds. I don’t exactly understand what you meant by “moral” and when morality became a decisive factor for a revolution.

Another point, in criticism of our dear friend’s statement, is that we have gone past reformism; I don’t think so. It has just become a slogan, and the reformist approach is still present in new forms. This approach is even still alive among our comrades. For example, replacing people who were part of the Islamic Regime with figures such as Hamed Esmailion, Masih Alinejad, Mirhosein or Pahlavi. Or other facts that our comrades have mentioned in the “Communists of the Friedman era” published by Slingers. They rightly said that, unfortunately, this reformist mentality continues and is extremely dangerous. In my opinion, the biggest threat to the movement right now is this reformist approach, along with racism, which includes all these marginalized nationalities that are being oppressed, including Afghans. For example, Afghan people were killed in Jina’s movement, but even their photos have been removed from the casualty pictures. And many more groups whose presence has been eliminated.

Another issue I wanted to mention is that I didn’t say there is no solidarity. Indeed, solidarity has significantly increased. For instance, in the past, I was the only one in our village and tribe who had been imprisoned or threatened; later on, I was even expelled. But now I see, day by day, that the spirit of struggle is spreading, especially among students who have a large population there. However, other things have replaced the previous conditions, like associating their race with pure Aryan or descendants of Cyrus. These words may sound ridiculous to us, but this issue is intensifying amongst the Lurs in the south. There are even some families of the victims who try to connect the blood of their children to the blood of Cyrus. So I think racism is an important issue and is being intensified through this propaganda. For example, they criticise the son of the Shah for not being the same as his father because the Shah did such and such.

Moving on, I would like to emphasise that the mentality of reformism is still alive among our comrades. An example of this is the alliances they make and the Charter of Minimum Demands published earlier. These alliances will not lead us anywhere. Or another example is pitying the poor or having pity on the victims’ families and being passive towards their sometimes reactionary attitudes. In my opinion, without determination, and I don’t mean determination for a specific cause or person, I mean intellectual independence, and it is very dangerous if it’s lacking.

As my last point about religion, I mentioned, the decline of religious belief or religious scepticism doesn’t necessarily contribute to the movement. We’ve seen religious individuals participating in the movement, but we have also seen religious people being part of oppressive forces. On the other hand, uprisings in Balouchestan are progressing for religious motivations. So we shouldn’t even touch on such a topic. This doesn’t mean deceiving people; It means that freedom is one of the main pillars of the “Woman, Life, Freedom” movement, and it has opened ways for individuals of every religion, belief or faith to join this uprising.

The politicisation of religion is what has become problematic. If we continue to focus on religion and equate it with the ideology of ruling power, it will only fuel Arabophobia. On the other hand, Zoroastrianism could be embraced as a political religion. Meanwhile, we have to consider the Balouchestan issue, our comrades from Zahedan are here, and they can explain better. However, the consequence of this view on religion is ignoring Balouchestan’s Issue; and, like many others, failing to support them simply because they gather around Makki Mosque without considering their other potentials or alternative meeting places. The mosque is not just a religious symbol for them, it also serves them as a safe haven. For example, when a woman whose daughter has been raped seeks refuge in the mosque, she raises awareness about the issue, by initiating discussions and drawing attention through the media. I think we have to take a better, more accurate and open-minded stance towards this issue.

Jiyan Group (JG): Our comrades in GRC raised a discussion on solidarity among the nations and overcoming chauvinism. I understand the importance of this topic and the progressive role of Jina’s uprising in this regard. But by emphasising solidarity, we should not overlook pluralism. I know that this wasn’t the intention of our comrades. For example, the debate around using “national oppression” or “nations” instead of ethnicity, which the oppressed nations insist on, is not merely a language matter. It is actually because of their subordinate position against the dominant nation. This is a small example, but it’s worth being mindful about. Suppose I go back to the last discussion we had in the first round; About finding the balance between diversity and maintaining the integrity of the movement while considering the dominance of nationalist discourse in Iran. We must be very cautious when it comes to ethnic or national solidarity in Iran. So that it does not turn into a tool to further suppress those who are already in the oppressed position.

There is another aspect to consider on this matter. We should not solely confine the economic issue to a figure we know as the working class. The economic issue also affects marginalized genders, it is also influenced by the contrast between the centre and the periphery and the oppression of minority groups. In fact, I want to emphasize the need for a broader perspective on the economic issue and even the working class itself as the subject. It means that economic exploitation takes various forms in the geography of Iran. As mentioned by our comrades from SMG, even housewives are subject to a form of economic exploitation. That is, categorizing these minority groups and confining each of them to a specific form of oppression can potentially lead us astray from a strategic standpoint.

Another friend from JG: I want to talk about the point raised by our friend from RRYCM. That the middle class has an insignificant influence on the movement. And also, the question was raised by another friend from SMG about the criteria and definition of the middle class. We need to answer these questions to be able to comment on their presence and influence in the movement. We pointed out this issue based on our observations of the central areas, and our perspective has been region-specific because observing central areas can lead to a class distinction approach based on geographical regions.

An important issue that was also mentioned earlier is that in recent years, specifically over the past twenty years, as the working class is becoming poorer, the middle class is also shrinking. We are witnessing a transition between social classes. I want to emphasize that the analysis we provided was based on our observations. Considering the discussions we had about the diversity within the Jina uprising, there are certainly various forms of pluralism and diversity among the revolutionary forces.

Another point I would like to emphasize is the concept of the “middle class” itself. If we aim to discuss this more precisely, we must carefully examine what we mean by the middle class. As political activists, we are having a conversation here and sharing our observations and experiences with each other. But the terminologies must be precisely defined so we can discuss them based on precise and accurate definitions.

Another point I would like to add is that this categorization itself is problematic. For example, when we say “middle class”, which gender or age group are we referring to in this economic or social situation? In fact, all of these factors are involved. One flaw in this kind of observation is its sensitivity to cultural elements. When we observe, we don’t go and ask someone about their occupation or their level of income. Instead, we often see cultural patterns, such as their clothing style, behaviour, and other similar things. Therefore, a term like the middle class can be a trap.

Javad Nazari Fatahabadi’s Committee (JNFC): The point I wanted to make is that when we use the term “middle class” and refer to the past twenty years, we should consider that this term was used during the period of reforms to smuggle a portion of the working class into the middle class. For example, this terminology sometimes implies that we are dealing with the lower middle class. But what does the term “lower middle class” mean? They divide the middle class into three parts: upper-middle class, middle-middle class, and lower-middle class. They do this to expand the concept of the middle class and give it a subjectivity so that it appears as if the working class is smaller in comparison. Whereas if we consider a factor such as waged labour, a significant portion of society has become wage earners today. Then another aspect would be the question of ideology and ideological inclination. For instance, should a wage earner with a reformist or Pro-Pahlavi ideology be considered part of the middle class or working class? Because class interaction encompasses both material and ideological aspects simultaneously.

I acknowledge the thoughtful consideration of our comrades in JG regarding the term “working class,” which may sometimes carry a masculine connotation in leftist discourse. The term working-class man in the industrial context specifically refers to industrial labour and often excludes non-industrial labour from the working class. We should be sensitive and mindful when we use the term working class. Housewives are also part of the working class. It includes teachers as well, who are referred to as “unproductive labour” in leftist academic discussions, but ultimately they are part of the labour force. Similarly, housewives are also considered as labour forces and all of these groups belong to the working class.

The problem with the term “middle class” is that it has been tainted by the post-1990s reformist literature in Iran. I do not deny the existence of the middle class, nor do I want to deny the existence of a class and claim that it doesn’t exist at all. But fundamentally, it is not as extensive as it’s commonly understood, and as mentioned by our comrades from JG, there has been some interchange between social classes. For example, during the 8 years of Ahmadinejad’s presidency, many of them (the middle class) have become wage earners, and their mindsets/thoughts have changed. In the course of these revolutionary changes since 2017, people’s perspectives and ideologies have been transformed. Again, I accept the concern of our SMG friends that we are still facing the danger of reformism as a kind of virus that can also exist within the left wing. But this is separate from adopting a concept under the name of the “middle class”. I just wanted to remind you that when we use the term “working class” among ourselves and refer to class analysis, this is what we mean.

For example, the reformists insist on attributing the November protests to the subjectivity of the middle class and claiming that the middle-class was present in these protests. This is why we need to consider these two factors: the wage-earning factor and the intellectual orientation. In relation to intellectual orientation, someone from the working class can be both a wage earner and be pro-Pahlavi. But we cannot categorize them as a middle class only because they have a pro-Pahlavi stance and conclude that the middle class has expanded. I only wanted to raise the point that this reformist hegemony in social class analysis has unfortunately existed since the 1990s. Without a thorough examination of the concept and definition of class, we will be caught up. For example, Asef Bayat is still using “the poor” in his talks but he also uses the term “middle-class poor” which I think is problematic.

Red Revolutionary Youth Committee of Mahabad (RRYCM): The truth is I did not think the middle-class issue would be this complicated otherwise I would have employed a more correct word. In our view, there are two classes: the capitalist upper class and the working class, the class that is being exploited and has nothing except their labor force that even they cannot sell. In the beginning, I mentioned from the perspective of Kurdistan, especially cities like Mahabad. We cannot have a nationwide analysis, and when I said the middle class, I meant those who are doing fine, can provide food at home, can travel once a year, and are relatively, not perfectly, in a better place [than others]. I did not also mean [to call them] petit bourgeois, I generally said those things and of course I did not need to because we were supposed to have a general analysis, not a specific one and I apologize.

In terms of the issue of ethics, this is not a reformist issue. Let me tell you something that happened about two months ago. We were standing in a line among around 400 other people when I realized the merchant or petit bourgeois whom the government had given him the exclusive privilege of storing and distributing a series of goods to people, is unjust and unfair. I went ahead and threatened him by saying I will ruin this building on your head if you do not stop this. Thus, by saying ethics, I do not mean we should not employ violence in an appropriate instance [like this], I meant that a suitable proceeding, a suitable act in a suitable time and suitable place and suitable condition induces us ethically as fighters (I do not like the word activist), as leftist and communist fighters to be able to gather the masses around us. The issue of ethics in our view is to be able to show the notion of revolution in a more realistic description to those conservative layers [of people] who are still in doubt and are not sure about the Islamic Republic or are influenced by the media of the Islamic Republic or the right-wing opposition. For instance, if you capture an officer and penetrate a stick in his butt and that becomes disseminated in the media, especially at a time that we are not in a balance of power, or if you kill, trouble, curst or threaten someone with the most hideous manner, I do not find it attractive and qualitatively furthers masses of people from the meaning of the revolution. I do not see any relation between these considerations and reformism. For example, in the case of that officer [bank security guard] who killed the clergy (AbbasAli Soleimani, a member of the Assembly of Experts for Leadership from Babolsar) a few days ago [in a bank], it was an ethical and qualitative action. It was clear that there was 400 billion in the clergy’s bank account while that officer could not afford to have even eggs in his house to make dinner for his guest the night before. I do not see any ethical problem in this matter.

Zahedan Revolutionary Youth Core (ZRYC): I think it is necessary to have a separate discussion about the poor class and the middle class. This can be very useful in my view. In Zahedan where I live, there is not such a class as middle class, I even can say there is none in Iran and there are specific reasons for this. When you consider the poverty line, those who are situated under the poverty line, are part of the poor class. We have a community that is the upper class. Where is the middle class here? You give it a description and say, for example, those who are intellectual, those who in my friend’s words are doing fine, can be put into the middle-class format. I personally agree to divide the classes into a few categories. For instance, we divide the poor class into a few sections: the upper poor class, the middle poor class and the poor class that are at the bottom. It could also be the same in [the case of] the middle class, however, we cannot use this description for the Iranian society unless you separate the question of intellectuals from the question of living conditions.

In the case of the question of ethics and reformism, in my view, it is difficult to define ethics while in the fight. When you are in a fight, you must be very careful. For example, if you lost your friend in the fight and have suffered emotionally, although you did not suffer from bodily or financial damage, still can be very effective. Here ethics loses its meaning. I have a suggestion for the continuation of this discussion. There was something in everyone’s conversations that I found interesting. For example, they pointed out the question of Arabs or Tabriz (Turks), my suggestion is that every one of us presents a general report on the existing condition of our regions and with this in addition to our views, we would introduce our environment a bit as well. For example, one of the friends used the term “Molana” to speak about Mr. Abdolhamid[1] that carries an honorable attitude. I have an issue with that. We can define and familiarize [each other with] and say who this person is, what he has done and is doing, this might change these definitions. This might change your opinions about us who are active in Zahedan.

Slingers: Thanks comrade, this is a good suggestion. As we describe in our invitation, for this series of roundtables, we tried to invite a combination of participants whose belongings are diverse in terms of gender and repressed nations so the discussion can be unpacked in different directions. So, such a tendency is plastered in comrades’ arguments, but your suggestion is good and can be employed and discussed in detail about regions. If even the group decides, this section can stay here and will not be published. It is possible that all comrades agree with me that this discussion can be fruitful.

Gilan Revolutionary Committee (GRC): I wanted to explain a point that one of the comrades brought up. I think I could not convey what I was intending in my last turn. The issue is that we are speaking about a movement and an uprising that occurred in our society and the opposite side is a state that is suppressing in different shapes and by various powerful tools. When we bring up the notion of solidarity, I was not talking about the community of Kurdistan or the community of Azarbaijan to discuss the repressed nations, I was speaking about a specific attitude in the Azarbaijan community that is chauvinistic, I was talking about a nationalist and ethnocentric tendency. If you paid attention to the social media that they have, in Twitter and Telegram channels, they constantly mentioned that ‘When did the Iranian society including Persians and other ethnic groups defend us so that we come to their defense? This movement is not related to us at all, or the support of a Kurdish girl has no business with the Turks and Azarbaijan community.’ And things like this that for example ‘the Woman-Life-Freedom has a Kurdish root, and we should not support it.’ Our argument was that our society has passed these impediments and we witnessed that the commemoration of Jina was very crowded in Tabriz. We witnessed on her 40th day [after she passed away] that sections of [Tabriz] streets like Shahnaz Street and other places were occupied by people for hours and it was interesting that far progressive slogans like Live Kurdistan, Live Azarbaijan were chanted. Thus, our argument was in relation to the analysis of the condition and situation that we are currently facing in Iran. The issue of reformism is the same. We must consider the general condition of the society. Yes, there is still a streak here and there but when you speak to people, and you are in the society talking to the masses of people, you realize that today nobody has any hope for any fractions of the government. We saw this in the people’s low participation in the [presidential] election as well and this is still the dominant mode. The matter is the whole society, not here or there. Or the fact that a section of the left has a reformist standpoint, is not part of my argument here. I just wanted to explain these points. Another comrade from our committee will discuss a few points.

Another comrade from the Gilan Revolutionary Committee: This discourse brings forth a series of pertinent matters, which, while not devoid of significance, can be considered a side issue. Examples include discussions on racism, the value judgment of religion, or the Middle-class discussion. Undoubtedly, these questions warrant attention; however, I contend that the primary concern lies in addressing the query posed by Slingers’s comrades. Let’s answer primarily from the perspective of class interests, and let’s explain the current situation of society in terms of where it is in this historical period in terms of class struggle. Besides, let’s answer a series of questions that are more secondary but not ineffective. In my opinion, after the 1978 revolution, the war adversely affected the movements. Given the prior dissolution of the councils, they used the pretext of war to suppress any movement.

Later on, after several years of development era, whenever someone wanted to speak out or protest, they were told to be patient because it was a time of development and progress, and the authorities were constructing and building. Despite being protesters, large segments of the population believed that the discussions and obstacles created by the governments of that era were justified. Later, class contradictions reached a stage where nationwide protests took shape in 2009, and the movement took to the streets and became more expansive. However, if we examine the trajectory of the class struggle movement during that time, we can observe that reformists primarily led this movement and its leaders were mainly reformists. Those who were arrested were primarily reformists, those who were from Islamic Iran Participation Front (reformist political party). The Green Movement was at the centre of the struggle during that period.

In the following years, the intensification and deepening of class contradictions led to the involvement of the lower classes in the movement under the pretext of rising fuel prices or other resentments. The movements of 2017 and 2019 culminated in the recent uprising. We can observe a progressive growth circuit if we examine the trajectory of class struggle throughout this period in different sectors. Previously, the focal point of the struggle consisted mainly of the middle classes, who had superficial complaints and lacked deep social dissatisfaction. For instance, they were dissatisfied with the lack of newspapers or people needing to queue properly for buses and bakeries. They belonged to a relatively privileged class, although they gradually entered the realm of struggle due to the severe political repression they faced.

However, the movement has shifted towards the lowest strata of society and the working class. From my perspective, this is a hopeful development. This implies that the movement is not only dormant but has found a deliberate subject of struggle within the broader society. It predominantly centred around the efforts of the youth within society. Notably, this focus on youth activism was not inherently negative; in fact, it held significant value. However, the movement is now progressing towards an authentic class-based struggle, wherein the working class, if willing, can consciously contribute to its continuation. Suppose the working-class desires to stay informed and actively participate in this struggle. In that case, it can be a positive development that expands the struggle and draws other sectors and classes, such as women, students, and oppressed social groups, into this authentic class struggle. It can be considered a promising development, and we should delight in it.

Therefore, I would like to emphasize that not only has the class struggle not ended, but it has undergone a slight shift. The form of class struggle visible on the streets may have experienced a temporary decline, although variations can still be observed everywhere. For example, women’s struggle against compulsory Hijab represents a political matter and a form of political protest.

Therefore, I believe class struggle is flourishing, becoming genuine, and expanding between a class that constitutes the majority of society, with the expectation and hope that this class becomes organized and united. Women form a significant portion of this class and play a prominent and influential role in these struggles. These are all indications that gender discrimination, gender differences, and national differences are gradually disappearing, and a relatively Pleased unity has been created among different segments of people, nationalities, and genders. I no longer see anyone in society teasing a woman. Society’s social consciousness has transformed and grown, although there are still weaknesses, which is natural.

In response to the question of our current situation, it must be said that class struggle has intensified and delved into the depths of society, which should be seen as a positive omen. Peripheral issues, such as whether we have a middle class or not, are not things that we can analyze according to our own desires. These are existing realities worldwide. The middle class is a part of the social entity; we have the capitalist and working classes, and between them, various layers engage in business and earn their livelihoods, and in the objective and real sense, they are the middle classes of society.

Apart from our will, this can be divided into three layers or sections, as Marx suggests. The effluent layer is close to the bourgeoisie class, the middle and lower layers. The last section, quantitatively and qualitatively, constitutes the majority of this class. They are the potential allies of the working class in our future struggles for fundamental transformation and a social and socialist revolution in society. This is provided that the working class can engage in principled, organized, and united struggle, rallying and aligning itself with these oppressed classes and defending their interests. The signs of this can be seen now in statements like “We are the children of workers, we stand by their side” among students or in the struggles of women who are in sync and solidarity with the working class of Iran in various places, advancing their struggles and highlighting their slogans. We also see the shifting focus of nationalities towards advancing the national issue through the channel of class struggle and the hegemony of the working class. These are the things that, if we want to analyze Iran’s current situation, are immensely promising or give us hope for these conditions.

Regarding the statement that a friend made about revolutionary violence not being accepted by some people yet, or that revolutionary violence, which has existed in various forms of people’s struggles for years, became more intense and prominent in Jina’s uprising. Revolutionary violence should be noticed from the perspective of the interests of the working class when this class enters the scene and struggles for advancement in conjunction with the class. The goal is not for people to accept or reject violence or to engage in violent acts Occasionally. While I do not reject revolutionary violence, I believe it is revolutionary when it accompanies the masses’ struggles within the framework of society rather than being separate from it. Any violent struggle that is disconnected from the level of mass struggle is not beneficial for the revolution.

Let me give you an example. One of these cities was in Kurdistan, perhaps Mahabad, Bukan, or Oshnavieh, where the people took control of the city and threw out the belongings of the municipality. However, later on, they did not know what to do. Then the regime came with a show of force, bringing all their armed forces to the streets, trying to instil fear. Afterwards, our friends who were there, facing the risk of their lives, sought refuge in other cities, asking for help, saying that the army had arrived and was left alone. While there was fighting in the streets of different cities, as far as our interactions with people around us were concerned, we would ask ourselves, “What should we do?”

We had reached a critical situation. In circumstances where the level of struggle throughout Iran was not at its peak, they escalated the level of struggle to a point where they were now seeking our help, and we didn’t know what to do other than engage in nightly and daily fights, being on the streets, and chanting slogans. What I mean is that the struggle in any form should be proportional to the collective movement of the masses, and at the forefront of those struggles should be the workers’ class struggle, which we hope will grow and expand. We argue that class struggle has become extremely intense in society, and the government has become a robust tree composed of various units that exploit and oppress the working class and the masses severely. On the other hand, the masses have become weary of their lives, suicides have increased, child labour has risen, and all of this is influenced by the growth and deepening of class contradictions and the brutal exploitation and suppression of workers and the people. Religion and racism and all of these issues are also raised in this context. We should not give so much importance to these secondary matters; we should focus on the central points.

I would like to mention a few points regarding the Charter of Minimum Demands. Considering our discussion, where I see the goal as fundamental and socialist transformation in society, and in this regard, the shift of struggles from the capitalist class to the working class, I see everything in this context. Therefore, if I see a movement somewhere that leads to greater unity of action and closer proximity among political activists and even different social classes, I welcome it. Although if we scrutinize each clause of the charter individually, we can find many flaws if we focus not only on the depth analysis, which is essential in itself, but also on the expansion of various forms of struggle and unity among social, class, and political forces, meaning prioritizing the expansion of class struggle and involving more social classes and political parties, the charter is effective in its own way and brings together many parties. People who couldn’t even sit together and interact with each other are now sitting side by side.

This is a good example of workers who were workers in the literal sense and have spent years in prison. However, from the perspective that they do not align with the left, apart from the fact that leftists are also caught up in their own circle, they have distanced themselves from socialism and the left. Unfortunately, signs of pacifism or surrender can be seen in them. Now, the very movement created by the Charter helps them find a sense of enthusiasm, and they hope for its expansion. Therefore, look at the role of every social movement in its own context. The Charter does not aim to create a complete social transformation; it seeks to take a step forward. Despite all the criticisms it faces, it fundamentally unites activists and socialists, and this is just the beginning. It needs to be expanded in various dimensions. I believe it was a positive move in its own right.

Because you perceive that anyone with a positive view of the Charter is likely a reformist who accepts reforms, we are not opposed to reforms; reform and improvement are necessary. The struggles carried out by the working class for better wages and their continuous efforts in that regard can be seen as a form of reform. However, this does not equate to reformism, which implies a lack of consideration for revolution and fundamental transformation. Alongside this, we should strive for societal transformation, demand the revolutionary overthrow of the government, advance these movements, unite them, and pursue our aspiration for fundamental transformation.

Street Militant Group (SMG): First, as Marx points out in his class analysis, the question of different nations should be considered inside of the working class. He mentions how the working class must be united, brings up the question of Poland, Germany and England. And you cannot ignore the class-based complexities that is integrated with race, ethnicity and various nations. You cannot bypass these paradoxes and analyse the class issue mechanically. You cannot precisely solve the complicated issue of class without looking at the questions of religion, nation and women and just move on. I am stating a few short examples. Among workers in Iran, many are Afghanistanis. But based on our observation in addition to the people who participated in Jina’s uprising and movement and the reports from people in prison, there is a serious issue of anti-Afghnistanis and anti-Arabs. Or the conflict between Arabs and Lors in Haft Tapeh or oil and petrochemical bases which are currently the pole of workers’ strike in Iran. Second, I never appraise religion as good or bad and we have freedom of belief here. Marx that you mentioned, has said that religion is the opium of the masses that will naturally subside. Because of this you cannot take away the worker’s religion without presenting any alternative, because that worker gets back home tired and needs something for consolation and religion would mediate that. It was well said that our genuine discussion is not religion. I too agree that our exact contention is a political religion, but you just leave the issue without any alternative. We do not position against the Islamic Republic in this matter that you are chanting against me. The main point is what possibilities we do and we do not have. I said a few points about religion and class and mentioned that we must look at the complexity of class issues in relation to nations, women and religion. We cannot shift without seeing these issues and end by saying the question is merely a class issue. At least go see the signers in the Charter of Minimum Demands. I do not know and cannot see where this unity among activists exists that the charter claims to have created. The middle class that the comrades say doesn’t exist, I see in Fars province likewise in Tehran that the majority of those who participated in the movement are lower middle-class; a section of them are teachers.

In the case of violence in AdelAbad, NematAbad and Javadieh that [the protesters] rightly, rightly broke into the banks and stole the Kurosh store, they might not explicitly know that they are financial symbols of capitalism, but they know that the ones who suck their lifeblood, are these banks and financial institutions and they correctly put them in a fire; I am not going to evaluate here, good or bad. [That is] what we saw less in Jina’s movement. In the case of Abdolhamid, I did not appraise Abdolhamid whether this human is poison or not, or whether he is good or bad, I did not appraise him at all. I mentioned a general viewpoint regarding the question of Baluchistan based on the contents I read from Desgoharan and what I have observed there. And I become very happy if the comrades from Zahedan speak about Abdolhamid now or later or present something to increase my understanding of these issues. I look at the Makki Mosque where individuals gather around it including Khodanour whose mother is saying that he went to pray when killed or [like] other killed individuals in Baluchistan. But when we associate middle-class issues with ethics, it suddenly becomes dangerous where I see working-class women work for example in the service workforce, then spend most of their income buying make-up items or clothes so they can be employed for jobs in another place. This means that this class on the surface is resembling the bourgeois class and petit bourgeois class. If you mean that middle-class ethics are capitalist ethics, I say that ethics are not something that you say exist here or there. There is a capitalist competitiveness in such a place where a working class who sells their prison bed to another worker; or a leftist who emphasizes their individuality and identity and in competition with others, speaks of this idea today and that idea tomorrow; such competition is also a kind of capitalism. In my view, these issues do not contain any ethical dimensions. I do not even see any ethical dimensions in killing that clergy; that is also for subsistence because [the clergy] is his looter. Let us consider the Oghaf Institution where the clergies are their main stockholders. based on the last statistics, there are three thousand vacant houses in Tehran that belong to the Oghaf Institution, or the same phenomenon exists in Mashhad, or around the Shahcheragh in Shiraz where they are ruining the old fabric of the city for [developing] Shahcheragh. These are all associated with clergies and so are all subsistent issues and have nothing to do with the notion of ethics. Otherwise, capitalist ethics is propagated among all of us. I am seeing it in us undertaking daily competition, domination and elitism, and competitions among numerous groups. In my opinion, we do not want to either praise and worship anyone in this roundtable or shut our eyes and chant that reformism has been terminated. We came here to this roundtable to exactly understand why Jina’s movement was discontinued, and why did the chemical attacks on students become that much accentuated but the support was shallow. During these chemical attacks, teachers like Mohammad Habibi, Jafar Ebrahimi and other teachers were arrested or subjected to more intense pressure but we did not see considerable support for students from people except one school where mothers were guarding in order to protect it.

I did not want here to appraise the class issue or say whether the middle class is bigger or working class. I mentioned earlier that the group of unstable workers had the upper hand in this movement. If those unstable workers’ parents were wealthy, they are now counted as poor. I did not say at all that the poor class are not in the movement, but I saw in poor regions of Tehran, Fars province or Khuzestan [province] fewer people came out except Izeh that has always been revolutionary whether when they said no to Khomeini or when they did not let Khamenei in the city, and the Arabs have strong dominance there. If I want to see the class issues mechanically, I should say here that Arabs are oppressive, and I stand behind Izeh. But I want to solve the ethnic and national issues here so the unity of the workers is achieved. [I would] say to that Arab worker who fights with the Lor worker, these are exactly the same patterns that capitalism is laying out to create space between workers so they cannot create solidarity, and our important issue here is solidarity. When we see a religious individual or group participating in a protest, I do not associate them with the Taliban; well, they have their own beliefs. I cannot immediately take away their religiosity, I cannot tell them not to be religious but participate in Jina’s uprising. My argument is that any group has the right to be in this movement around these three words, woman, life and freedom, but what we can do to surmount these conflicts and gaps between different groups.

Another Comrade from Street Militant Group (SMG): Hello to all. I wanted to briefly say that we still hear taunts and are teased and harassed. The sexual harassment is not less in society. The gender question is still a significant issue. When you ask middle-class housewives why your participation was low blaming them why you’re not coming out [to the protests], we must pay attention that they were not allowed to come out. Most middle-class housewives were saying we were not allowed to go out of home at all. I must think about their liberation not just chant that there is widespread solidarity. No, there is not, I do not see that solidarity. I mean solidarity is more in some areas and in other areas declining where are especially very important like the severe racism, sexism and antireligion [other than Shi’ism]. Women among the intellectuals are saying that they say the world is in the hands of women but [when] I am at home, my partner or husband is still harming me. We cannot ignore these which are especially important and vital issues.

Jiyan Group (JG): I wanted to briefly speak about the notion of the generality of conflicts like national conflict and gender conflict. I do not want to be obsessive with words but assuming racism as a secondary issue, even just in language, does not take us to a good place. A clear example is the situation in Kurdistan and Baluchistan in relation to the movement. In my view, it is neglecting the national question by just seeing overtaking [the fight] in Kurdistan as a tactical case. Each section of the geography of Iran contains its own political tradition and economic and geographical situation and when we do not show the appropriate amount of sensibility to these objective differences, derived from various types of exploitations within the geography of Iran, as a result, things are said like you are overtaking, you are going fast, and go slower to be with us. The exact material analysis is that we see the overtake is the result of conditions there and of course has a tactical dimension, but it is not something necessarily under our control or merely a matter of agenda and tactics. I gave this example to clarify this matter that how its roots are objective and how it can affect objectively. In my view, we should not lag behind the leftist movements in the 50s and 60s (1970s and 1980s) that accompanied the glowing movements in Turkmen Sahra and Kurdistan. They managed to connect the national and class questions, and by establishing cultural-political centres, the cultural dimensions of the national question also were not discarded. I wanted to actually say that we have this learned lesson from the past.

Zahedan Revolutionary Youth Core (ZRYC): I wanted to mention whatever I am saying in disagreement with others, does not mean I stand in front of them or find them disrespectful. I am stating my views and others [can] agree or disagree. Following the discussion, I do not agree with these sentences insisting to say that the revolution is stopped and did not and will not continue. The revolution is continuing. Where is it continuing? [Where] women are carrying out disobedience regarding hijab; men are doing it too. This is a dimension of the revolution. The next step of the revolution could be this where we have gathered now and exchanged ideas together. If this is not revolution, what is it? The fact that workers and workers’ groups are on strikes, can be the next step of the revolution. The revolution is continuing in my view. It is not like to say that we go to the streets today and a revolution happens tomorrow or in 20 days. Revolution is a long-term plan unless a special and unpredictable happening takes place, otherwise we have so much work and [need to] put in so much labor. Another issue is assault against women. This would be foolish to imagine that every problem would be over, and women’s liberation is given to them in the aftermath of revolution [even] when hijab laws have been abolished. When the laws are defined and you have legal support [for women’s rights], it does not mean that everything is over, and no assault will not be happening. It is not like that. Let us not forget that because of the cultural, religious and traditional formations that we have in this country, the work of confronting the assaults and rapes will begin then. Another important question is when solidarity is talked about and is said that needs to be formed, what is the reason for this solidarity? We are not in solidarity with the fascists, we do not even become friends. I will not be shy; I personally will not be in solidarity with a group that is against people, against the collective opinion and against women’s rights. We are clearly on the people’s side; we have no business with whoever says something unlike what people say. I am sure they do not have a social base. Do not pay attention to their media shows. Why does Reza Pahlavi’s group, the Mahsa’s Charter group, make this much noise? Just because they have media power. We only have this media problem. If we had a media which would disseminate our words among people, we would surely be in a better place than them. We should not be involved too much in this media atmosphere. About the issue that our friend mentioned regarding the attention to geographical and cultural differences, the issue is exactly here. If we decide to ignore them, even if a revolution takes place, it would be unsuccessful. The reason why we are sitting here at this moment, is to become familiar with one another and our differences, move in the line of people and work collectively to reach our desirable results.

Gilan Revolutionary Committee (GRC): I wanted to mention a few small matters. One of the issues brought up, was in regard to gender and ethnic oppression and the question of religion. [Our] argument did not mean these issues have been solved but meant the movement managed to take one important step forward. Imagine for example in terms of those nationalistic viewpoints in Azarbaijan, or religion that has long roots in Iran. A major forwarding step was also taken in the views towards women. The matter is not that they are solved but at the same time, we must not forget what effective steps this movement has taken in these issues. It is brought respect for women and has created tremendous solidarity and empathy among the ethnicities. Humiliation and oppression against Afghanistanis and other ethnicities is clearly not solved yet and none of them can be solved in a capitalist society founded on exploitation. The argument was only about progressing on one important step.

Another issue [is about] a comrade who was worried what if a demand-oriented movement would begin, and hoped this movement does not become a demand-oriented movement and was understanding this as going backward. I wanted to say if we accept that there is a battle on interests happening here, we should know that the unveiling hijab [of women] is the interests; At times [they] are individual and social freedoms and in another case for example workers’ strikes, are for subsistence. This war is a war of interests and the working-class movement has its own features, its own processes, and its own ups and downs. If we look at it this way, not only do we not worry but also, we become happy that one specific demand related to a class is brought up. These demands at times look small; it sometimes wants integration, other times the right to organize or strike that both are very social and very political. If we see this way, not only do we not worry but also, we become happy because a class which could be determinative and transformative, wants to be impactful in the movement. I want to add another thing regarding what our friend said that the gender oppression issue should not be merely seen through class. I feel some women activists forget that women are a large portion of the working class. When we say class, a larger chunk of the oppressed working class are women. Thus, it is not like we put something aside and call it women [rights] and workers are men who work behind the machines. Women are actually a great portion and a bigger portion of the working class. Here I would like to note another friend’s comment about teachers being the middle class. I do not think it is a right statement. Teachers, nurses, housewives, unemployed and most of [workers in] pseudo-jobs are great portions of this family that are positioned in various sections of this class.

Slingers: In the end, I would like to explain why I did not interrupt and control comrades’ conversations. I was thinking I wish this opportunity became possible sooner and I hope comrades also agree with me that these discussions are important and necessary, at the same time productive. I tried [to allow] the arguments to be developed and all comrades fully discuss the aspects that they thought, are important so, we can directly and unmediated hear each other’s opinions after a few months. Each of the comrades is representing committees that unlike some so-called paper groups, are real committees that are acting and fighting in their work and life environments. My imagination was [in this session] the discussions should be opened sufficiently so comrades from different committees become familiar with each other’s views to be able to continue next sessions.

Appendix

[1] Abdolhamid Ismaeelzahi is an Islamic Sunni cleric in Baluchistan, Iran. He has been conducting the Friday Prayers in Makki Mosque for a few decades in the city of Zahedan, one of the largest Sunni communities as well as one of the most underdeveloped regions in Iran. He has recently taken sharp and progressive positions against the Islamic Republic’s brutal suppression and is standing on the side of people and is explicitly supporting the movement of Women-Life-Freedom. He has received tremendous admiration from a wide range of political oppositions while his past work and positions maintain serious doubts for many leftist, feminist and progressive groups.

Comment here