by Babak Ameli

Ever since its existence, the United States waged wars against different people of the world. The very foundation of the United States is based on war and genocide. Latest since the war against Vietnam, US administrations are constantly either waging war or threatening countries with a possible war. Within this political and economic logic, the US also uses a certain type of language of war, a genocidal language, a language that normalises power that leads to death and humiliation, a cheap language, a Hollywood genre language, highly patriarchal, highly colonial. But not only views the US any people outside its borders that does not act in its benefit as superfluous and illegitimate, its economy is also based upon millions of so-called “illegal immigrants”, people that have to endure life and work in the US without papers or any official status. Following Trump’s election and intensifying deportations and state violence against migrants, the Sanctuary Campus movement emerged in solidarity with the nearly 240,000 undocumented college students in the US. This movement also gradually confronted core elements of class and power leveraged by universities to reproduce the state and capital. In this article, we present some of these experiences and how this movement transformed the university as a commons nurturing non-capitalist modes of relations with migrant justice movements and communities.

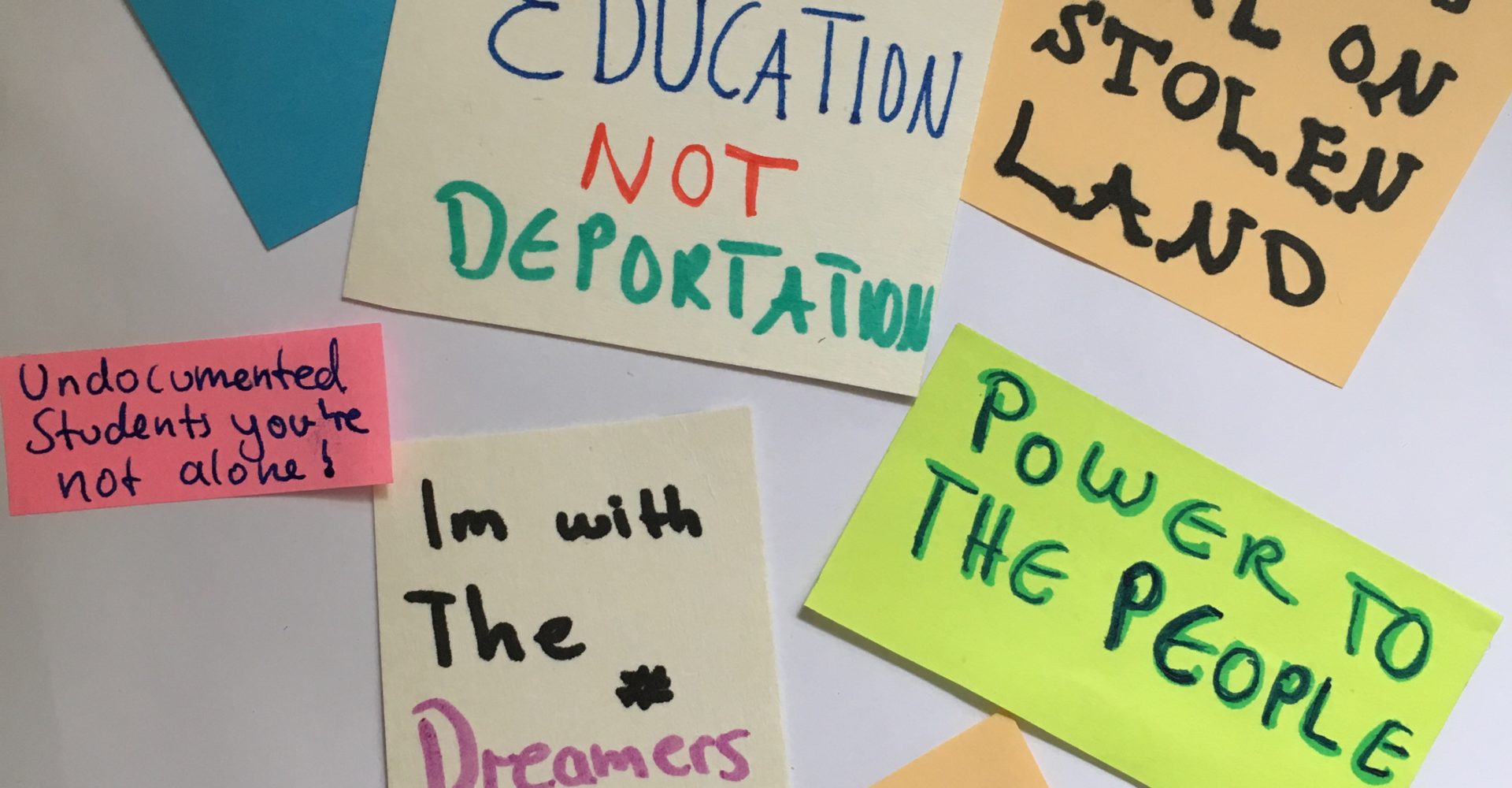

The Trump electoral victory In November 2016 sparked high school and college student walk-outs, sit-ins, and marches across the US. Students then self-declared sanctuary campuses that demanded of university administrators to refuse access to immigration enforcement on campus, no longer ask students of their immigration status, offer legal, medical, emotional, and logistical support for students suffering from exposure to law enforcement or racist attacks, and other demands that varied between campuses. In addition to immediate demands protecting the nearly 240,000 undocumented college students in the US, the Sanctuary Campus movement has confronted some of the core foundations of class and power leveraged by universities that reproduce the state and capital.

Insights and experiences in recent campus organizing efforts are critical in understanding the neoliberalization of universities and efforts to destroy racism, sexual violence, economic exploitation, and other forms of violence on campus beyond liberalist frameworks. The recent sanctuary campus effort also brings to the fore the potentialities and limits of migrant politics within the academic sphere. This text shares our experiences and analysis from two campus organizing efforts.

Context

Prior to the election of Trump, universities were being confronted by student protests around racism, sexual violence, and investments in fossil fuels. These actions were inextricably linked with Black Lives Matter, Standing Rock, and radical Feminist formations off-campus. Campus administrators responded by censoring and shaming student survivors of rape and Black student organizing efforts were being subdued by “conversations” and “town hall meetings.”

Off campus, Obama was deporting more immigrants than any other president in US history, neo-nazi groups were gaining new members, and state governments were passing laws criminalizing renting and employing undocumented workers. Much of this backlash was attributed to the 2006 May 1stImmigrant Strike involving millions of mostly Spanish-speaking workers. However following Trump’s election, immigrant students and university staff mobilized against the state’s efforts to target undocumented youth, students, and migrants from the Middle East and North Africa. Over one hundred campuses mobilized around the Sanctuary Campus demands and more than 30 universities agreed to student demands.

Other Sanctuary Campus efforts went beyond their demands to physically open their campuses to immigrant communities needing legal and medical support without the consent of university administrators. Such a conception of Sanctuary actualized solidarity between campus students and workers with the wider immigrant community that until this point, maintained an ambiguous relationship. Universities have been notorious for lacking in affordable housing for students that would subsequently lead to their gentrification of immigrant communities, refusing access to migrant youth due to cost and citizenship status, and neglecting migrant worker calls for a living wage and health insurance.

The university is an essential extension of capital, leveraging the precarity and mobility of migrant labor to reinforce existing race and class relations. Here, moving beyond a demand-based politics and fully rejecting the authority of campus administrators in conceptions of Sanctuaryare critical if migrant students and workers are to transform the campus into a commons capable of reproducing the emotional and material needs of the larger immigrant community to resist precarization (i.e., criminalization, unstable employment, exclusion from healthcare or education). The university not only extends the state’s capacity of precarization, but is also the first to exploit such conditions as cultural capital to further “scholarly work” and its authority over discourses relating to migrant struggles.

The university’s contradictory processes of inflicting precarity while claiming to ‘study and discuss’ potential alternatives is reflective of broader state level modes of utilizing crisis as control of migrant networks. As described by Sandro Mazzadra, the creation of “irregular migrants – subjects that are at the same time produced as insiders and outsiders” is easily applicable to the university. It may accept undocumented undergraduate students, and even provide legal and financial aid, but reject their enrollment to its own graduate or medical schools or be offered a living wage on the basis of their undocumented status. Such practices are parallel to the broader “flexibilization” and individualization of cognitive labor within academia via adjunct faculty positions, self-funding via grant mechanisms, without the protection of any labor laws.

For liberal academics that attempt to speak for the Sanctuary movement, they, by meeting with university administrators, convening panels within the academe without including migrant students or calling for the immediate elimination of all university officials and policies responsible for the marginalization of migrant students, are (perhaps unknowingly) deepening their own extractivist stake in such a radical moment and neutralizing it.

Sanctuary campuses and the autonomy of migration

Efforts to press the university for the Sanctuary Campus demands gave way to a new basis of campus politics around migration mirroring analysis emerging from the Autonomy of Migration, described by Manuela Bojadžijev, Serhat Karakayalı, and Sandro Mazzadra. Here, migrant students and staff were emphatic about the need for self-organizing, speaking, and ridding notions of victimhood and political apathy. Rejecting the authority of university administrators and even some non-migrant activists, NGOs, and community activist “leaders” was critical in creating an autonomous sphere of politics that freely engages with desires for commoning and intersectionality. We describe some of these experiences and analysis below:

Beyond liberal frameworks around migration. Campus and city-wide actions went beyond singular identities and linked with labor, Black Lives Matter, prison abolition groups, and Palestinian solidarity groups to expose mutually shared concerns (law enforcement, prison industrial complex, neo-nazi violence, securitization of campuses). Rejection of liberal discourses around citizenship, including its ‘logical’ legal frameworks around integration, are crucial in allowing our communities to assume agency and create linkages with non-migrant movements during meetings, marches, strikes (May 1st, International Women’s Day), and direct actions both on- and off-campus.

In addition, culminating our efforts towards moments of radical action cannot be underestimated due to the potential for materializing transversal modes of politics. Participation by migrant networks in the May 1stimmigrant strike or International Women’s Strike on March 8thsignal critical ruptures to the creation of counter-power, linkages with other radical networks, and deepening of constituent power. When such actions exist beyond a single workday or only the workplace, and are present within our homes, bars, social centers, etc., they have the potential to weave early formations of the “commons” based on expansive social relations, cooperation, and resource exchange that untangles processes of precarization.

Reclaiming the university from its capitalist relations. Campus groups became aware of the intimate relationship of universities and the state/capital. University trustees serve as advisors to trump, were major funders of the trump campaign, and run financial institutions and corporations directly responsible for many of our current crisis – housing foreclosures, global arms sales, fossil fuels, prison construction, etc. Based on such findings, fundamental questions emerged (at least within our circles) around how a campus could still be a sanctuary if it had billions invested in so many spheres of capital leading to war, displacement, and exploitation of migrant labor? If it was conducting research or educating students in finance, surveillance, social psychology, or law enforcement? Highlighting and resisting such core capitalist processes within the University are key if formations of Sanctuary are to have any relevancy to a non-capitalist mode of life.

The campus as a critical site of anti-capitalist and migrant struggle. The Sanctuary campus has the potential to rupture presumed sites and temporalities of violence around migration (i.e., US/Mexican border, Lesbos) and exposing thedailyand localizedforms of violence imposed upon migrants within the Global North and its most liberal institutions (i.e., universities, NGOs). In addition to existing calls for universal access to safe spaces, healthcare, education, and living wages for all migrants, the Sanctuary campus has the vital role of exploring the complementary role of conservative/alt-right/neo-nazi policies with those of its university administrators/trustees in de-valuing migrant bodies for profits. As a result of such efforts, the campus has become a critical site of conflict against the state and capital in addition to the park, square, or government building.

Autonomy! Not integration. The contradictions of integration within the global north emerged as many (rightfully) opposed the so called ‘muslim ban’, but did so with the support of google, amazon, and wall st ceo’s who feared any disruption to hiring some of the most elite Middle Eastern student graduates paid at a fraction of a typical wage afforded to a US citizen and fixed for prolonged periods. Protests responding to a specific religious or ethnic migrant sub-group in isolation of other shared forms of violence against Black men and women and decades long deportations of Spanish-speaking immigrants are divisive and reinforce existing gradations of precarization based on race, gender, etc., by the global north. Lastly, a politics of migration centered solely around the right to enter the workforce of the global north is obsolete and we must fight for the spectrum of other rights critical for our survival (housing, education, movement, safe spaces free from police and fascist violence, healthcare, etc.). For many, the informal or network based economy embedded within our family and community units are crucial for our collective survival when we’re unable to access ‘formal’ employment. Threats to our informal networks by police, gentrification, immigration enforcement, and fascist vigilantes further individualize and de-value our bodies.

The sanctuary campus as a commons. The capacity for students and workers to transform their time, labor, social relations, and infrastructure for the political, emotional, legal, and medical needs of broader migrant justice efforts is a critical rupture towards conceptions of the university as a commons. The formation of the commons throughout the Global South rejects state and market forces in place of collective control over resources (e.g., water, farming, healthcare, education) critical for our survival and reproducing non-capitalist modes of life. The Sanctuary Campus has the potential to serve as a commons for the broader migrant community rejecting neoliberal and academicized conceptions of the individualized migrant, a victim devoid of any political subjectivity. Such a notion of the Sanctuary Campus as a commons instead links migrant students with more complex planes of political engagement – families, unions or workers centers, migrant marches/squats/occupations, community centers, etc. The migrant recuperation of the National Technical University of Athens in the Exarchia neighborhood intensified the possibility of a commons by liberating spaces and relations for housing, schooling for children, political actions, and safety from the police, neo-nazis, and mafia. However, one must be critically aware of the researcher, university administrator, and other immediate threats to our autonomy that thrive upon mining the commons for its creative knowledge production, affects, and modes of social relations.

The sanctuary campus a site of critical reflection. Migrants entering via Mexico or the Meditteranean to the global north are at very high risk of sexual violence, extortion, kidnapping, and involvement in narco-trafficking. Between migrants, conflicts over housing, food, or water may emerge due to the state’s gradations of who is deemed a refugee versus migrant. Within the global north, many migrants are subjected to exploitation by older generations of migrants. The sanctuary campus is essential as a site for militant research and critical self-reflection about exploitative and violent modes of relations present within our community that may discussed without fear of being coopted by the global north and prevailing orientalist narratives that further marginalize our political agency.

Comment here